effort

People like to say that lives on social media look unattainable and perfect, but whenever I see something that’s beautifully curated all I can see is the sweat: the money expended, the surgery and fillers, the workouts, the interior designers, the carefully selected objects, the hours spent setting up and filming and taking photos. I think the effort is what’s most interesting. I like people who try very hard, and I like people who attempt to conceal their effort, but I especially like people who let all their effort show. We are all Frankenstein monsters—patchwork quilts of past experiences—trying to pass ourselves off as whole and cohesive things. Femininity in society is especially like that: how you dress, how you style your hair, how you apply makeup, how you eat, what jewelry you choose. These are learned things, earned things.

Here’s what I know: if someone’s much better than you at something, they probably try much harder. You probably underestimate how much harder they try. I’m not saying that talent isn’t a meaningful differentiator, because it certainly is, but I think people generally underestimate how effort needs to be poured into talent in order to develop it. So much of getting good at anything is just pure labor: figuring out how to try and then offering up the hours. If you’re doing it wrong you can do it a thousand times and not produce any particularly interesting results. So you have to make sure you’re trying the right way.

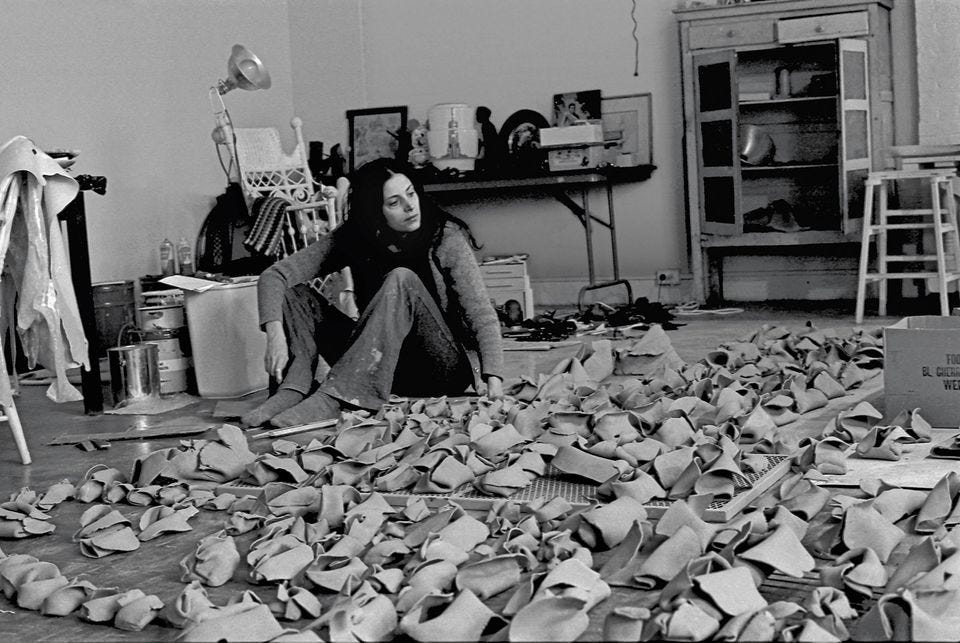

But this post isn’t about how to get good at things. It’s about how people always assume I’m interested in the end result—the wonderful thing they’ve made—when what I’m really interested in is the process. How did you get this way and why? I’m curious about the ugliness of trying, the years and years of wanting and hoping and working. I don’t know why I’m so fascinated by craft. I think it’s because it requires such a sustained tenacity. Like Michelangelo saying that he just chips away at everything that didn’t look like David: a hundred thousand little motions to reveal the underlying beauty.

I think a lot of people want to be but they don’t want to do. They want to have written a book, but they don’t want to write the book. They want to be fit, but they don’t want the tedium of working out. They’re ashamed of rejection and they’re ashamed of imperfection. I might want lots of people to subscribe to this Substack, but do I want to workshop a post every day? Donna Tartt once said in an interview that if the writer’s not having fun the reader isn’t either. I think people make the best things when they love the process, when they willingly shoulder the inherent uncertainty and pain that comes with it. It’s almost like a form of prayer: you offer up what you can even though the reward is uncertain. You do it out of love.

Fantasy is easy and effort is punishing. Seeming is always easier than being. But what kind of life are we living if we’re not honest with ourselves? My friend once told me that there are two types of people: people who are ashamed of something and choose not to do it, and people who choose to do it anyway and just hide it. I wanted to never be the latter: someone who cares more about appearances than they care about their relationship with themselves. I don’t want to pretend like I’m too good for ugliness, for effort, when I know very well that it’s the price that unlocks everything beautiful in the world.

When the Pandemic started bike sales surged in Spain because with a bike you could ride anywhere, thus avoiding the confinement restrictions and the daily curfews. Like many others I too bought a bike; at first I thought of buying an e-bike, but once you have a motor on your bike you end up using it most of the time, so bravely I decided to buy a normal road bike; I had not been riding since I taught my youngest 12 year old daughter how to ride a bike, and that was many, many years ago. Sant Cugat, where we live, is a very hilly area and I could hardly climb any hill; our home is at the end of a hill, easy to start downhill, but impossible for me to ride uphill, so I had to walk the bike home, very shameful; with age you lose muscle mass very fast an regain it only slowly. I started biking 30 minutes three or four times a week, always lamenting not having bought an e-bike. After six months I was able to climb some hills, and finally also our home hill, yes, in the lowest gear, but at least I had not to walk up. After a year of cycling I can ride almost all the hills of Sant Cugat, a big surprise for me. There remains a very steep hill to climb, from Sant Cugat to the top of Mount Tibidabo, the mountain that overlooks Barcelona, a 550 meters rise. Biking up to Mount Tibidabo would really be a big achievement for me; maybe I can do it in another four months, maybe not, I will try. What is the lesson I learned biking? We can do more and better than we think; start small, start slow, but keep going, time is your secret ally, and with time you will go faster and better, and you can feel proud of yourself.

I'm 74 and have never been athletic, but after 17 years of learning/practicing pilates, I'm pretty darn good at it. I'm not very good at languages, but am using the pandemic to learn a new one. I'm spending a little time each day doing the lessons. It feels good (I'm beginning to get it!) and bad (I feel awkward trying to speak it....). Yes, skills take time, diligence, and getting a kick out of learning. Thanks for highlighting this issue.