in praise of uselessness

I’m recovering from a flu and watching John Wick, a movie about a man who goes on a revenge spree because an asshole kills the puppy his late wife gave him. John Wick is my favorite movie, other than Phantom Thread, which is about a dressmaker who falls in love with a waitress. Being sick kind of reminds me of a drug trip, everything zoomed in and blurry and slow motion. I crank the heat up to 77 and wander around my own apartment like a zombie.

While I’ve been sick I’ve been unable to think. My mind feels both frenetic and inchoate. I’ve been entirely useless. But I’ve also been feeling that uselessness is not without its charms.

Uselessness is what I think of when I read the Didion line about “extreme and doomed commitments, promises made and somehow kept outside the range of normal social experience.” Useless as in: not practical. No easy path to financial or personal gain. Deemed pointless, perhaps even harmful, by others. Useless is how I describe the kind of gifts I like most: extravagant, beautiful, completely pointless. Useless is how I felt when I looked at you and thought: I will cast my lot in with you and if I’m wrong, so be it.

For many years of my life, what kept me dreaming was Cheryl Strayed’s words in this letter: “The useless days will add up to something. The shitty waitressing jobs. The hours writing in your journal. The long meandering walks. The hours reading poetry and story collections and novels and dead people’s diaries and wondering about sex and God and whether you should shave under your arms or not. These things are your becoming.”

At the time I wanted to be a writer, thought it wouldn’t happen for about 20 years, and was frustrated by my own uselessness, the long walks I would take through every neighborhood in San Francisco, the constant reading and daydreaming, the procrastination. I was around people who would work 12 hours a day and chew nicotine gum and go to the gym to lift weights three times a week and I thought I should be more like that.

I could not be more like that. I was not more like that. And that was okay. My uselessness, in its own way, became useful.

To pursue the useless thing, as I understand it, is to pursue the thing that is compelling only to you, not obviously remunerative, limited in scope. It was what I was doing when I started this Substack, which was just a series of musings I posted to Twitter, short with no obvious theme. Just sharing the inside of my mind.

It’s surprising how many people are resistant to doing things with no agenda. Often, when I ask someone why they’re not doing something they seem good at, they’ll say, “Oh, it’s not going anywhere.” / “I don’t have enough time.” / “I started too late anyway.” They would rather expend their time and energy on the sexier thing, the more obviously lucrative thing. And who could blame them? But that tends to take you along a less interesting route. I’ve always been partial to the Feynman line about studying what interests you in the most undisciplined, irreverent and original manner possible. On some level, giving yourself permission to be useless means giving yourself permission to do what you love. Many people see it as a moral failing to chase after what you like, if what you like seems useless—why be passionate why you could provide utility? But what’s utility without joy?

I love TV critic Emily Nussbaum’s writing, and I’ve always been struck by her account of how she got started. She was a graduate student at the time who had written some poetry reviews and book reviews, but hadn’t been passionate about it. But watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer for the first time opened up something new. From her book, I Like to Watch: I’d never finish my doctorate. Instead, Buffy spiked my way of thinking entirely, sending me stumbling along a new path. My Buffy fanhood was not unlike any first love. It was life-swamping, more than a bit out of proportion to the object of my affection, and something that I wanted to discuss with everyone, whether they liked it or not. I’d been an enthusiast before, but not a fan in the stalker-crazy-obsessive sense. I had other work to do, teaching and editing and, eventually, working as a magazine journalist, but for several years, the only thing I actually wanted to do was analyze Buffy the Vampire Slayer. (In 2016, she won the Pulitzer for Criticism.)

There’s something powerful about allowing yourself to fully, obsessively love something that makes no sense. And it’s so contrary to how we’re told to live our lives. Identify and capture value! Go into the field where the best jobs are! Marry someone who is reliable! I’m not saying that’s bad advice—it’s good advice from many a perspective—but I also feel like I’ve stumbled into everything meaningful in my life when I was just like, hey, I’ll just give this a shot and it definitely won’t work.

From Simon Leys’ lecture about reading:

Love and reading provide good metaphors for one another. There can be no meaningful reading without loving what you read. Nabokov was right to say that a book is either for the bedside table or for the waste-paper basket: either you enjoy passionately its company—so much so, that you cannot bear to part from it; or it does not mean much to you, and you should not be wasting your time with it.[11] And this is precisely the reason why literature and scholarship are so often at loggerheads. A 'literary scholar' appears to be a contradiction in terms: a scholar must read all the books that are relevant to his research—however mediocre, dreary and boring. A true lover of literature only reads the books he loves. The conflict between the two can sometimes become acute, and though there are a few instances of good writers who are also literary scholars, on the whole, there is little sympathy wasted between the two camps.

The heart of uselessness, I think, is love. I don’t know if you’ve experienced the kind of love I’m talking about, the kind that can’t be shown off as evidence that you’re worthy, can’t be converted into goodwill, makes the people who care about you worry you’re going mad. The kind of love where you think 20 times a day, “What’s the point?” But there is no point. But there is never going to be a point. It just persists.

I have loved books that way for much of my life and also people. I used to believe I had to articulately justify everything I chose to spend my time on. Still, I was never so good at sucking it up and doing the practical thing. As I get older, I more and more want to live in a way where I’m okay throwing pebbles into the void, okay pursuing what is unobvious. Thinking something is beautiful is enough.

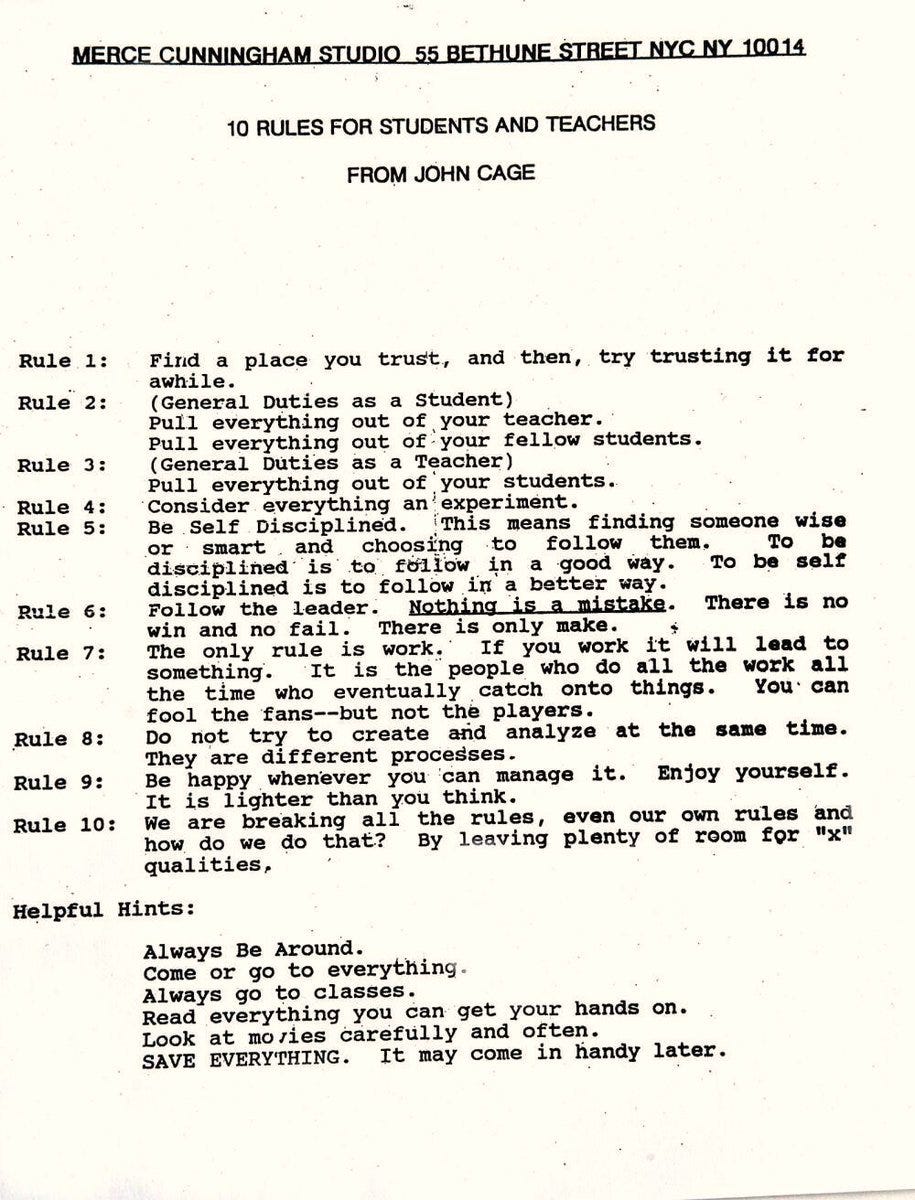

From Sister Corita Kent’s 10 rules for students and teachers: There is no win and no fail. There is only make. That’s another way of saying that nothing you love is truly useless, though it may appear that way for a very long time.

I love this—doing the extravagantly useless, pointlessly interesting, things is what makes life meaningful! the things that don't scale, seem to have no potential for for financial gain…and yet they feel so instinctively interesting and obscurely important to our lives.

It's a relief to pursue those things instead of constantly suppressing them because they're "useless"…sometimes we can't know what value they'll bring to us in the future

This was extraordinary! I get so disheartened when I think of life as a long line of to-do lists and safe commitments. (And course that’s important too, we can’t live without some practicality). But the things that most excite and engage me tend to not make sense (or money, ha-ha) and I love this reminder that pursuing joy in ‘useless’ pursuits is something we shouldn’t be ashamed of. Nothing you love can ever be a waste of time. Our lives aren’t meant to be leveraged into bullet points of ‘I did this to get this’. It’s a bigger and richer world than that.

Anyway blah blah, thank you for the post :)