on and off

A while ago I noticed that when I worked I was often distracted by tasks and plans and feelings, but when I ostensibly “relaxed” I was also trying to be productive. On weekends and vacations I’d be tense with thoughts of what I hadn’t finished, whom I needed to call, tasks I needed to do the next morning. To-dos crowded out other to-dos in my mind.

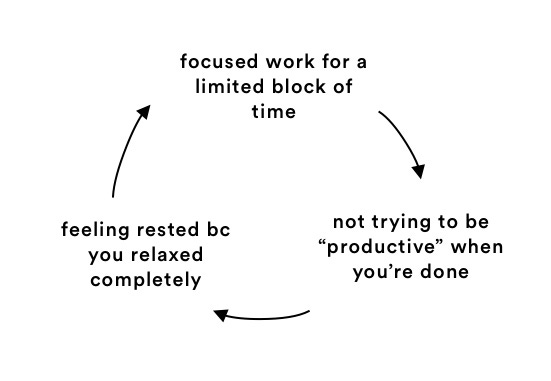

This felt like the natural result of having a full life, but when I thought about it I realized that the people in my life who seemed the most effective were really good at toggling between on and off. When they were doing something they were totally focused on it, and when they were done they stopped thinking about it. When they were with their friends they didn’t check their work notifications unless they knew it was urgent. When they went on vacation they actually went on vacation. The flip side of that was that they actually concentrated whenever they were working.

This ties in with an American tendency I’m deeply suspicious of: the fetishization of long working hours. In SF you hear it all the time: I work 12 hours a day, 14 hours a day. I don’t take lunch breaks. In New York… don’t get me started. I think it’s true that you can sustain that kind of prolonged intensity for limited phases of time (for ex, the first crazy year or two of a startup, or during a manic burst of creativity where you’re painting through the night for a couple months) but I think for most people it’s impossible to be completely focused for 12 hours a day over the span of five years. Question one: are you focused for 12 hours a day, or are you working for 20 minutes, checking your texts, taking a coffee break, working for 25 more minutes, checking Instagram, etc etc? Question two: if you’re actually focusing for 12 hours a day every day, how much Adderall are you on? I’m just saying.

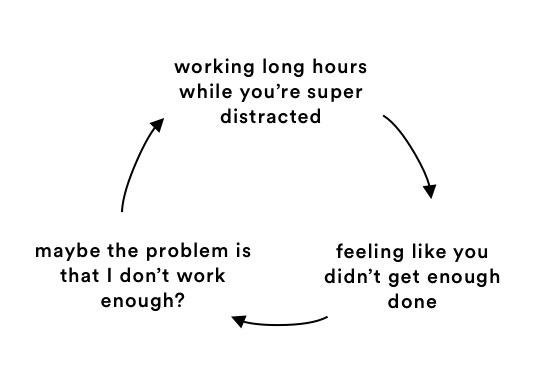

Most of us don’t need to focus 12 hours a day, but we still feel the pressure to perform constant productivity. Which leads to a lot of time appearing productive that’s actually diluted, half-hearted time where you’re not actually getting very much done.

One thing that helped me was reading interviews about other people’s writing processes. A lot of authors said things like “I truly believe it’s only possible to get four hours of good writing done in a day. After that the mind wanders.” And I thought, well, four hours isn’t very much time. What would it look like if I could carve out four hours of pure focused time every day?

It turns out that you can get a lot done in four hours, which further fed my theory that you only have to be totally focused for a remarkably short period of time. When you’re on be totally on, and when you’re off commit to being totally off. That way you can avoid the diminishing marginal returns of “working” when you’re super distracted and feeling like you’re never actually as productive as you want to be.

Few of us can live fully compartmentalized lives. If you’re me, you might be writing while you’re thinking about travel plans and worried about whether the puppy’s sick and you need to call your mom back and you’re meeting a college friend for dinner later. It’s hard to stop things from bleeding into each other when infinite distractions are available.

At the same time, I know that without moments of pure attention we lose track of our time and lose track of our lives. Put it another way: the only way we can remain coherent people in a distracted world is by forcing ourselves to focus.

One remarkable thing about the best athletes in the world is this exact idea. They are exceptional at switching on and off. It takes real discipline to keep things easy when they need to be and vice versa. Not many people can do it. We all know it: you grow when you rest, not when you exercise. It's the same for work. Rest is a key part of the productivity equation. To work better, harder, and be happy, you need to be good, then great, at switching off.

On Restful Activities

Becoming a Writer by Dorothea Brande (1930s) has a chapter on rest. She mentioned that writers often took busman’s holidays. That is, they write at work and read for pleasure. (This whole time, their brain gets burned out on words.) That’s why the ‘rest’ she recommends is doing something opposite from regular work.

In my case as a writer, when I feel I can’t bring myself to write another word, I apply what she said. Aside from exercise, meditation, and unscheduled travel, this worked for me: play a relaxing *wordless* playlist from a music streaming service then go stare at a blank wall.

The "stare at a blank wall" part is really important, especially in my room. (To be effective, you need to remove all the written words in your eyesight during this.) Whether I fall asleep or stare blankly doing nothing doesn’t matter (it still lessens fatigue).

Dorothea Brande recommended doing this until the words demand to speak out of you. Oddly enough, this lets me find the motivation to write and read again, it becomes something to look forward to.