the agony of eros: on limerence

"for my next trick, I will gaslight myself"

Howard Hodgkins, Ice, 2008-10

Hello! This is the next installment in my series on how love hurts and why. Recently the main character of Twitter was a woman who left her husband of 14 years after meeting a guy she really vibed with at a conference. She became convinced over the course of an evening that he was her soulmate. The title of her forthcoming book is When A Soulmate says No, so it turns out that he was not her soulmate. But why did she think he might be? Limerence.

The psychologist Dorothy Tennov coined the term limerence, which is the obsessive, all-consuming feeling certain people get when they fall in love. She writes about it in depth in her book Love and Limerence. The most prominent characteristic of limerence, as she explains it, is 1) intense fixation on whether your feelings are reciprocated and 2) obsessive preoccupation with the love object. Like: you wake up thinking about them, you go through your day thinking about them, you lie in bed at night thinking about them. From a paper on treating limerence with a CBT approach:

The greater the degree of uncertainty, the more intensely the individual ruminates about the LO, and the greater the desire for reciprocation. This pattern of uncertainty about the LO's feelings and availability may distinguish limerence from the early stages of a typical romantic relationship, in which both partners often experience infatuation or obsession with each other.

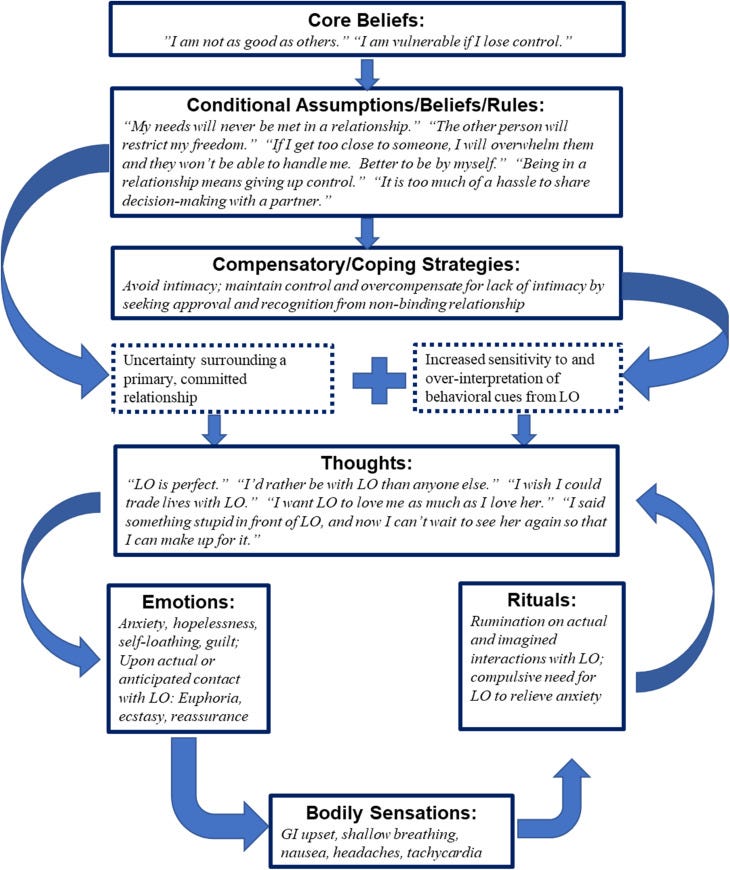

“Case conceptualization for development and maintenance of limerence” from the paper

Limerence can make people act insane. In her book on romantic obsession, Unrequited, Lisa A. Phillips described an episode of limerence she experienced when she was 30, and how her deranged behavior during it inspired the book: “My unrequited love became obsessive. It changed me from a sane, conscientious college teacher and radio reporter into someone I barely knew—someone who couldn’t realize that she was taking her yearning much, much too far.” In Agnes Callard’s essay The Eros Monster she describes an affair she was enmeshed in that sounds like as a classic episode of limerence:

It was torture. I rapidly found myself thinking of little else. I fell behind on obligations, forgot appointments, lost weight and sleep; a few months in, I began drinking. About a year in, thoughts of suicide surfaced—was that the only way out? I sought professional help. Therapy, for better and worse, equipped me to deal with the roller coaster, to accept it as my new reality. When I would complain, Hugolof himself would tell me to “just walk away.”

Sometimes I thought, and said, that I loved him. At other times I hated him to the point that, if I didn’t hear from him for a day, the possibility of his death conjured the tantalizing prospect of relief. It might seem incredible that you can hate the person you claim to love, yet that is exactly what happens when eros becomes a trap.

During the Hugolof years, my usually stable and mild emotions came to fluctuate wildly. I would conjure up tender charity and affection, having, just the moment before, whipped myself into bitter outrage. Superstitious thinking requires a massive investment of energy; the vacillation between hopefulness and despair is what fuels the perpetual thinker’s unending inquiry into what this or that new detail means. When everything out there is heavy with symbolism crying out for interpretation, one’s inner life becomes saturated with emotion.

Of course, not all people who are limerent end up becoming stalkers. In Tennov’s book there are many examples of people who become intensely limerent for coworkers or even lovers but never express it out of fear of scaring the person away. Picture a grade school crush where you stare at the back of a boy’s head and doodle his name on ruled paper but never talk to him for years. Tennov: “Just as all roads once led to Rome, when your limerence for someone has crystallized, all events, associations, stimuli, experience return your thoughts to LO with unnerving consistency.”

Also, some people never become limerent, which means they perceive people who do become limerent as totally unrelatable. If you’re reading this essay like “what the fuck is she talking about,” maybe that’s you! Which is wild, if you think about it: some percentage of people are being hijacked by this very intense neurochemical experience either once or multiple times throughout their life, about which endless songs are written and movies are filmed, and other people have no clue what it’s all about.

Some things Tennov observed about limerence:

The onset is difficult to predict and may happen in all sorts of circumstances. It can be sudden or gradual.

When people feel ecstatic union (“Love is a human religion in which another person is believed in”)—that’s limerence.

There’s an inability to be limerent about more than one person at a time.

Limerence is intensified by adversity.

Limerent episodes tend to last between 18 months and 3 years.

Sexual attraction is an essential component of limerence.

Limerence involves compulsive daydreaming about the limerent object.

Limerence is predicted on uncertainty; when you are sure of reciprocation, it naturally disappears over time.

Wishing you weren’t limerent does not help you become less limerent, lol.

Tennov identified three ways in which limerence disappears:

Consummation: Your feelings are returned, and therefore you become less preoccupied over time.

Starvation: It becomes clear over time that your feelings are definitely not returned (though you might spend a long time fantasizing that they are), and the limerence gradually fades.

Transference: You find someone else to be obsessed with.

People who are anxious tend to experience limerence more often than people who are not; it bears a lot of similarity to anxious-preoccupied attachment. This paper “exploring the lived-experience of limerence” suggest that the people we become limerent from are influenced by our parental figures:

The idea of a construction of a LO type that emerged from a variety of early caregiver memories, might also explain why a LO often fails to reciprocate or fulfil the desired emotional connection (or at best sends mixed messages of reciprocation). Specifically, LO selection in Limerence appears to involve some yet-unformulated mix of early caregiver triggers and unmet emotional needs which parallel, yet supersede, the normative more successful factors of mate selection, examples being physical attractiveness and compatibility of values and interests (Berry, 2000; Rubin, 1973). Indeed, one respondent specifically linked the idea of childhood attachment figures, separation anxiety, trauma and self-identity and in this sense Limerence may involve creating imaginary companions (Taylor, 1999; Taylor, Carlson, Maring, Gerow, & Chaley, 2004) and/or later maladaptive fantasy with extensive structured immersive imagination and disassociated states (Bigelsen & Schupac, 2011; Dell & O’Neil, 2009) as a form of coping, whereby imagined emotional reciprocation and proximity reduces anxiety and facilitates temporary relief.

Tennov calls non-limerent love “affectional bonding”:

Informants who described what I came to call “affectional bonding” usually replied affirmatively to my initial question about whether they felt themselves to be in love. But unlike those whose relationship was based on limerence, they did not report continuous and unwanted intrusive thinking, feel intense need for exclusivity, describe their goals in terms of reciprocity, or speak of ecstasy. Instead, they emphasized compatibility of interests, mutual preferences in leisure activities, ability to work together, pleasurable sexual experiences, and, in some cases, a degree of relative contentment that was rare (even impossible) among persons experiencing limerence.

It generally seems that it’s impossible to maintain limerence in a healthy long-term relationship (it’s a mechanism to induce pair bonding), so when people who have been together for 20 years say they’re “in love” they’re referring to affectional bonding, not limerence. Maslow described it as D-love versus B-love:

Maslow wrote of “D-love,” which he said was not love at all but a state of dependency. “B-love,” in contrast, should be welcomed into consciousness; it is never a problem but can be enjoyed endlessly. It has beneficial effects on the persons involved since it is associated with individual autonomy and independence. B-lovers are not unreasonably jealous and they are not blind. It is the other, damaging D-love which blinds you. In true love (B-love) you are able to perceive your lover clearly and penetratingly.

Limerence is the feeling of being possessed by desire. When you ask people about being limerent it’s not atypical to hear “It almost ruined my life,” sometimes followed by “I miss the intensity of it.” If you want to freak yourself out, check out the Limerence subreddit, where you can see posts like “Honestly if I could punish someone, I would make them limerent for the rest of their life. It’s the most slowest and painful way to die.” From the paper:

Theme 3: Disintegration of the self. The respondents regarded Limerence as a disintegration of the self in that a state of turmoil develops which manifests as uncontrolled, turbulent emotions. These included feelings of confusion, destabilisation and being out of control, even to the point of stalking a LO. All of the respondents recognised Limerence as an emotional rollercoaster, which the following respondents describe below.

[Limerence as...] Elation and despair (R5).

Rushes of fondness and excitement and false hope (R4).Euphoric feelings of love, combined with guilt, self-condemnation and confusion (R3).

Limerence inspires a lot of art. Books that are about limerence: Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux, I Love Dick by Chris Kraus, What We Do in the Dark by Michelle Hart, 22 Minutes of Unconditional Love by Daphne Merkin, The Ravishing of Lol V Stein by Marguerite Duras (honestly all of Duras, if you ask me), Anais Nin’s diaries, Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina. “Ruin me, but do not leave me,” wrote Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich to the courtesan La Bella Otero: that’s limerence. Henry to Anais: Anaïs, I am going to open your very groins. God forgive me if this letter is ever opened by mistake. I can’t help it. I want you. I love you. You’re food and drink to me—the whole bloody machinery, as it were. Lying on top of you is one thing, but getting close to you is another. I feel close to you, one with you, you’re mine whether it is acknowledged or not. Limerence!

I never knew how to think about it: as a real emotion, or as an involuntary chemical reaction. I guess it’s both. For many people limerence will be the strongest emotion they ever experience, the feeling with the most amplitude. In Unrequited, Phillips describes her friend Katherine, who finds herself in constant unrequited crushes which seem to lead to nothing but frustration: Heather Havrilesky described it as a “prayer to a closed door.” When Philips describes Katherine to another friend of hers, the friend “countered, “That’s the kind of fantasy that my therapist would say was completely unrealistic and neurotic, and there’s nothing good about it.” Phillips goes on: “This view is understandable and common. But it ignores the value of the emotional honesty of allowing yourself to feel love, even when it can’t be returned.”

On a podcast discussing her essay, Agnes Callard talks about how Plato believed that obsessive love for another person could sometimes be successfully be converted into a non-possessive love of the beauty you see in them, which you can then appreciate in all other places it appears in the world. I love that idea—the thought that a self-centered obsession, an intense experience of projecting desire onto another person, can become an appreciation of the good within them. We are all, in our own time, capable of turning our internal preoccupation outward.

It’s insane how the impossibility of it makes it more intense. It feels a bit like love comes down to choosing between “very intense love that only happens in your head” or “actually possible but more grounded & therefore not feeling quite as special love”. The romantic age unfortunately pushes us a lot towards seeking the former.

“For many people limerence will be the strongest emotion they ever experience”

this is breaking me